- Home

- Tanguy Viel

Article 353 Page 2

Article 353 Read online

Page 2

In exchange, you’ll just have to maintain the grounds, Le Goff told me—the mayor’s name was Le Goff, see. He was offering me a place to live and all I had to do was mow the grass and trim the hedges, and when the place was eventually put up for sale (given the commune’s finances, that was the plan, to sell the château someday), I would show people around. I still remember how he came to see me one evening to give me the news. After we’d swapped a few remarks about the drizzle coming down, he looked at the ground and muttered, as if it cost him more than me: So we’re going to sell.

And I asked him, As is? You want to sell it as is?

Yeah, as is, we’re selling it and we aren’t touching a thing, we’re leaving everything, along with the spiders who’ve spun their webs and the resident ghosts, whoever buys it gets everything.

So I said: What about me? Will I have to leave?

It won’t change anything for you, Kermeur, you’ll just have to make an arrangement with the new owner, because the five acres will belong to him.

Then he added, And if your finances improve, then…

I knew very well what he meant, and he knew very well that I knew that my finances were due to get a lot better very soon, as soon as I got the layoff bonus from the Arsenal shipyards. It would be a fresh start for me, for me and a few thousand other guys, since in the last three years they’d laid off four-fifths of the workers.

The Arsenal will be closed in less than ten years, I told the judge. In less than ten years, it’ll be nothing but a memorial downtown. Maybe there’ll still be high fences and cops at the gate to keep people out. Maybe people will wonder what’s going on inside. But it will actually be empty, all that’ll be left are forgotten motions, dusty machines, and missing workers. I’m not saying it’s good or bad, just that it hit us pretty fast. But all those quick layoffs didn’t cause much of a stir, much less strikes or protests, for the simple reason that for once the city or state government, or both of them, didn’t quibble about the layoff terms. Everyone got an average of four hundred thousand francs as a separation bonus, and you have to think what four hundred thousand francs meant in 1990. It was the price of a little house here in Finistère.

Even the shop stewards and the militants had to admit how smoothly the slow, eventual closing of the shipyard was happening. Most of us, the moment we were laid off, started spending our time reading real estate listings or looking at boats in showroom windows, not haggling over an extra twenty thousand francs.

Still today, when you walk the coast trails high over the ocean, even during the week, you’ll see a lot of guys who look too young to be retired standing tall at the helm of their fishing boats out in the channel, fighting the current and the waves kicked up by a contrary wind, and later proudly spreading their catch on the dock, because in the ten years since they were laid off they had to do something to occupy their mornings—mornings, because you have to get up early if you want to go fishing, see, and haul up your pots before someone does it for you. But I better not start talking about fishing, I told the judge, because there’ll be no stopping me, and anyway, that’s not why I’m here.

That remains to be seen, said the judge.

I didn’t answer, because I don’t have that gift that judges and lawyers have, of firing words into the air like cracking a whip. Anyway, it’s not as if I hadn’t told myself a thousand times that with the money, I too should buy myself a good fishing boat with a motor powerful enough to get through the waves at the harbor entrance. Also, I’ve always thought that if worse came to worst, if life really got hard, I could always live aboard, at least temporarily, it would be like a shelter, I told myself. I could see myself living out my days in the cozy cabin of an Antares or a Merry Fisher tied up to a dock in some harbor. But that’s not what I did.

No, said the judge. That’s not what you did.

Otherwise I wouldn’t be here, I said.

No, said the judge, otherwise you wouldn’t be here.

It felt weird to hear him say that, like it was sarcastic, or, I don’t know, like he was turning the knife in a wound in me, and he was opening it without my knowing if he was doing it for fun or if he was just following the straight line of facts, if the straight line of facts was also the sum of all the things left out, or abandoned, or unfinished, if the straight line of facts was like a series of wrong answers to a big questionnaire.

In any case, I was in a good position to see Antoine Lazenec coming, with those pointy shoes of his. I don’t know why, but I’ve never liked shoes with pointed toes, those Italian shoes that look polished even in the rain. And it’s not like I was in the habit of starting with people’s feet when I met them, but I was cutting the estate lawn and had my head down watching the mower move across the grass and not hearing much of anything around me. So the first thing I saw were his leather shoes on the path, and also because they were so black and shiny against the white gravel. So I looked up and saw a guy, not too tall and almost bald, wearing a black jacket with his shirt collar open like a Parisian. He was looking at me without really smiling, waiting for me to turn the mower off. When I cut the motor there was this sudden silence, and he just said, Is all this for sale?

I could hear him jingling keys in his pocket while he looked at the château, as if he had taken in the whole property at a glance, the five acres facing the sea and the old freestone building, in a single “all this,” and was already appropriating it. I could see his ivory or cream-colored sports car behind him gleaming in the sun, because it was sunny that day—see, we do get sunshine around here sometimes.

Yes, it’s for sale, I said. The château and the five acres of the grounds, it’s all for sale.

There was a silence as the two of us stood in the shade of the building, me wiping the damp grass off the mower blade, him standing in the calm weather—there was hardly any wind that day—with his hands still in his pockets.

I could tell he was expecting something, so I said: Are you here to see the place?

That’s right.

Do you want me to open it for you?

No, he said. I’m waiting for someone.

So there we were again, between two awkward sentences, one keeping an eye out for whatever he was expecting, the other looking at the orchard descending toward the water, the first apples already bending the branches, and Erwan playing with his soccer ball under the trees a little farther down. So maybe because neither of us knew where to look, and maybe because I didn’t dare start the mower again, because at times like that you try to find something to hang your thoughts on, like a coatrack, anyway he started the conversation again, and said: Is that your son?

Yes, I said.

He seems to like soccer.

Yes.

Are you a soccer fan?

Pretty much.

What’s your son’s name?

Erwan.

How old is he?

Ten, going on eleven.

He was starting to look impatient, glancing toward the road to see if anyone was coming, with his hand still in his pocket, jingling his keys. At that point, I didn’t think he was more likely to buy the place than anyone else, because I’d already seen a few of them coming, guys in suits with wallets probably bigger than their hearts, but when I showed them inside and we went into the big medieval hall and they saw how dilapidated it was, most of them backed off. As time went on, I wound up thinking I’d be able to string this job along forever, showing the château like a tour guide to people who would never buy it, and living there in the groundskeeper’s house until the end of my days.

The place was maybe five hundred square feet, set back from the sea where it blew pretty hard sometimes, but it had thick stone walls, and the living room and two bedrooms were enough for the pair of us, I mean Erwan and me, even if it didn’t get much light and dormice nested in the fiberglass, and even if the pine needles kept the grass from growing in

the shade of the evergreens’ branches; there’ve always been evergreens here. In winter the pines keep what little light there is from reaching the living room or the kitchen, at least other than filtered through the trees, as if they were dumping their load of green and brown needles right onto the kitchen floor tiles, but it never bothered me. I’m like that too, like an old evergreen.

Erwan sometimes says that now, that I’m an old tree unable to move, probably with the same dry, almost poisonous old bark, which has been putting down roots under the walls all this time. Erwan grew up so fast these last years, amazing how they change, our kids, we barely blink and suddenly they seem as old as us.

How old is he now? asked the judge.

Seventeen. I should have said only seventeen, as if the past six years had lasted as long as twenty. Now that those years have passed, and especially all those visits I paid my son each week, with him behind the glass in the visitors’ room, I see the whole story differently, you understand. But that day, on the estate with my mower tipped over and Erwan holding his ball, the day Antoine Lazenec showed up, how could we have foretold our future, Erwan’s and mine, written on his skin? I don’t usually judge people at first glance, so for me he was just an ordinary visitor, the kind we often got of a Saturday afternoon, taking advantage of the fact that the place was open to come have a look.

It was only when we heard hurried footsteps on the gravel, and I saw Martial Le Goff coming up the path, that I realized this wasn’t usual, because the mayor didn’t usually come to greet a possible buyer, much less apologize for being late, the way he did, out of breath from having run, as if he were afraid of missing the start, all sweaty because of his weight. Le Goff was pretty fat, the way you’d imagine a village mayor to be fat, with the high color you’d imagine a mayor’s face to have, kind of like my own high color, and for good reason. We probably did the same amount of drinking over our lifetimes, and often together. We knew each other well, all those years on the town council voting for projects together, all those lobster pots we hauled up together in his little fishing boat, when you could spend the whole day on the water doing nothing but watching the shadows of fishes under the surface.

And we were neighbors. From my bedroom, I could make out Catherine in the distance peeling her vegetables at the sink, with Le Goff in the foreground having a whiskey while he watched the news on TV.

And we had the same first name. It’s funny, we’re both called Martial. So besides being on the same side politically, that brought us together. Le Goff and I were close, is what I’m saying.

And he was a good mayor. He was a good mayor for the whole peninsula, once. But it’s been a long time since Le Goff was a mayor, or even a man, God rest his soul. But that was sure to happen too, I told the judge, at least one person would wind up like that. A suicide.

The judge didn’t react. All the time I was talking, shooting sentences into the air like arrows, looking to see where they would land, what file they would hit or bounce off of and spread across his desk like so many future tales, he didn’t react, no sir. And yet the echo of the bullet from Le Goff’s hunting rifle was still ringing through the whole town, without the reasons for what he’d done being brought to light, or rather without anyone wanting to. The local reporters just made a few cautious suggestions stuck under vague headlines like “The Peninsula Suicide” or “A Mayor’s Strange Death,” hinting at drinking or marriage problems. But that wasn’t it, I said. Martial didn’t have a marriage problem. If anyone had a marriage problem, I told the judge, the guy found sprawled on the ground some morning would have been me.

He didn’t react to that, either. His face was getting harder and harder to read. He was letting me talk my head off any which way, a thousand thoughts crowding into a funnel whose inner laws of selection maybe he was trying to understand.

Anyway, Le Goff was still alive and very much the mayor on that Saturday when Lazenec and I saw him coming up the road, hustling as best he could along the gravel path, twice apologizing for being late while mopping his face with his silk handkerchief. I could tell the two of them knew each other well, at least to judge by their friendly gestures and the way they used each other’s first names—Martial for one, Antoine for the other.

Did you two introduce yourselves? asked Le Goff.

No, I said, not really.

So after a moment the guy, the one I sometimes call the cowboy, finally looked me in the eye, put a fairly firm hand in mine, and said, Lazenec. That was it. He didn’t say a thing about himself, as if that statement alone was enough to put his name in lights. Except that I’d never heard that particular name, much less known I was supposed to greet him like the messiah, at least for all the reasons that Le Goff would explain later, after Lazenec had left. You have to tell me what’s going on, I told him then.

Yes, you have to tell me what’s going on, I said when Lazenec had left after touring the estate, going through all the rooms without paying much attention to anything, it was as if he was showing us around, with him leading the way through the rooms and hallways. I remember that when he looked out the upstairs windows, he said, There’s potential here, several times. You were right, Le Goff, there’s potential. Looking at the land sloping gently to the sea, with the pine trees lined up in a sort of royal path to the water, he said he liked it very much. And he repeated that word, “potential.”

Standing there at the old oak windows with his back to us, it was as though he had taken in the sky, the view of the channel, and the whitish city stepping down like a staircase, already taken all that in at a glance. Even now, he was trapping Le Goff’s name as he talked. I wouldn’t say I disliked him that day, that’s not the right word, and even if something dark had been written on the windowpane, even with invisible ink, it would have been noticeable. I’m not one to shine spotlights from the recent past to illuminate the present, and I know very well that there’s no compass come up from the bottom of the sea to show us the way. Often it’s just the opposite: The present is what shines its light into the great depths of the sea.

As I think back on it, you know what strikes me the most about that visit? His ordinariness. That’s right, ordinariness. The kind of guy you see in the street carrying a briefcase and maybe it’s full of banknotes or kilos of cocaine, but what you think is, just insurance policies or frozen-food catalogs. Except maybe for his sports car, the likes of which we don’t often see around here. It was a Porsche, to be exact, and even then I wouldn’t have been able to tell, except that Erwan was there. Erwan came along on the whole tour, and later, when Lazenec drove off in a cloud of white dust, Erwan said, It’s a Porsche, a 911. And, all of ten years old, he added, Is he going to buy the château?

So I looked at Le Goff and repeated what Erwan said: Is it true, he’s going to buy the château?

Le Goff looked at me in turn, opened his eyes wider than usual, and said, Kermeur, don’t you read the papers?

I could have answered that yes, usually I did, only sometimes I felt a little tired…In fact I hadn’t bought the newspaper that morning. So Le Goff pulled that day’s paper from his back pocket and unfolded it under my eyes. It had a huge headline saying something like “Big Plans for the Peninsula,” and underneath it a photo of a balding guy with his shirt collar open, so I knew right away who it was, not to mention what he had in mind, because next to it was an interview that talked about all the plans in question. So I looked over the whole page as if I were already searching for the answer to a puzzle, and I came across words printed bigger than the rest that kind of exploded in my head, sentences with strange expressions like “real estate complex,” “rental investment,” “residential estate,” and then off to one side lower down, like a kind of feverish conclusion that the reporter felt was worth stressing with an exclamation point: “a seaside resort!”

Imagine that, I told the judge, a seaside resort here on Brest Bay! And I continued reading the article line by li

ne, with its big sentences like all the region lacked was the faith and courage to face the future, there was undeveloped potential here, it said, for generations we’ve been sitting on a gold mine covered by cabbages and artichokes, a new era of tourism and development was dawning, it was time to prepare to enter the new millennium, so that by the end of the article you’d think a kind of archangel had come down from big-city heaven to deck our consciences with flowers. First to weed them properly, our consciences, then plant seeds in our brains in the hopes of growing a boulevard, or even better, five-story buildings all glass and exotic woods with solariums, glass elevators, and heated swimming pools. But the expression that echoed in my skull wasn’t “building” or “solarium.” It was “seaside resort.”

It’s not as if we aren’t used to this, having some crank appear from time to time and look down his nose at those of us who live here, saying we didn’t how to make the most of our landscape, our miles of coastline without a hotel-restaurant or campground worthy of the name, or upscale apartments to enjoy the view, that beautiful light that hits the rocks in the late afternoon, the calm of the ferns that seem to absorb all the wind’s pain…I could talk these places up too, and I love them more than any little speculator in the world ever could. The fog that comes and goes under the pale sun. The leaves of the trees when the storms move off.

But you don’t live with things by shouting their praises in newspaper columns.

There on the château grounds, with the Porsche long gone, I took the time to read the whole article. And I told Le Goff that it was unbelievable, just nuts, that I should be the last person to learn about this.

Said the mayor: Kermeur, old man, we haven’t seen much of you recently.

I remember trying to understand what the word “recently” implied. True, I’d kept pretty much to myself these last days, watching too much television or something, hoeing my flower beds next to the stone walls without bothering to look at the road or the town, or anything that was happening behind my back, as it were. After all, I’m nearly fifty, so digging my garden and looking after a son seemed like more than enough.

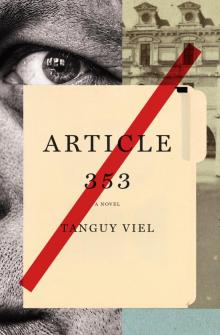

Article 353

Article 353