- Home

- Tanguy Viel

Article 353 Page 4

Article 353 Read online

Page 4

Easement? I said. What’s an easement?

Le Goff was the one I turned to at that moment. He couldn’t have expected to hear a word like that used but he wasn’t about to contradict Lazenec, so he stammered, casting about with “that is to say,” and “in the end,” and “you see,” so that I eventually understood that “easement” didn’t mean that I was being eased out. But it did mean something like a pebble in your shoe.

So the guy, the cowboy, who kept his hand in his pocket, eventually looked me in the eye and said: Yes, of course, we’ll have to discuss that. And then, to change the subject—I don’t know if it was instinctive or not—he looked at Erwan and asked if he liked soccer. You understand, I told the judge, he didn’t say, “Don’t worry” or “We’ll work something out.” No, he’d noticed a ten-year-old boy with a red-and-white fan scarf around his neck and asked him if he liked soccer. Erwan looked at me as if he were hesitant to answer, because that’s the way he was, Erwan, kind of shy.

Imagining Erwan as shy might strike you as odd today, but I assure you that if he could have hidden in my pocket at that moment he would’ve done it, to the point that I was the one who answered, I was the one who said, Of course, yes, he loves soccer.

I didn’t bother telling Lazenec that we were season ticket holders at the stadium, that we wouldn’t miss a game for anything in the world, seated up there in the fan section with the cheering and the cold and the air horns blasting in the night. I didn’t bother telling him that we had already seen him, Lazenec, in his glass luxury box on the heated levels reserved for local big shots. There he was with his collar open as usual, chatting with the club president or the owner of some supermarket whose name was written in big letters on the players’ jerseys, while we pulled our anoraks up to our necks in the north grandstand wind. I didn’t bother saying that the first time we had seen him was that same afternoon when he first visited the château. Sitting in the north grandstand, we recognized Lazenec, or at least Erwan did. He tugged on my arm and pointed to him, up there in a box, saying, That’s the guy from this afternoon, and so I looked at the stadium boxes. And then I better understood why Le Goff followed him around like his shadow. What I should’ve thought that evening, and what I’ve learned to think since, is that it’s never a good sign to run into twice in the same day a guy you didn’t know the day before.

There in the mayoralty hall, as the crowd began to thin out and people left with their prospectus and their seaside-resort dreams, Lazenec bent down to Erwan like an old family friend and said: I’ll take you next time, if you like. I’ve got seats in the central skybox, and the players come to see us after the game.

So try to imagine, I told the judge, just try to imagine the light shining on the harbor the day he drove up in his sports car and took Erwan to the Brest Stadium’s manager’s box. At the far end of the stadium that night, huddled against the wind, I saw my own son nice and warm behind glass, with hostesses bringing him orange juice on a tray, with Lazenec next to him, and the two of them sitting beside the club president. Try to imagine that at the end of the game, instead of his going home with the rest of us—a little drunk by now—the players came to the box and gave Erwan a jersey they had all signed. Open his closets today and you’ll find at least a dozen of those shirts. He even has a jersey signed by Juan Cesar. Can you imagine?

I don’t know anything about soccer, said the judge.

Yeah, of course, but it’s just to say that this whole story—

This whole story is mainly your story, said the judge.

Yes, of course. It’s mine. But let me tell it the way I want to, let it be like a wild river that sometimes overflows its banks, because I don’t have a lot of knowledge and laws like you do, and because in telling it my way, I don’t know, it eases my heart a little, as if I were floating, or something like that, maybe as if nothing had happened or even, and maybe especially, as if as long as I’m talking, as long as I haven’t finished talking, then right here, right in front of you, nothing can happen to me, as if for once I could suspend the cascade of catastrophes that has been crashing down on me nonstop, like dominoes I took years to patiently set up that were collapsing without warning, one after another.

Anyway, it wasn’t long after that before we started seeing guys in flannel suits roaming the subdivision streets and sitting down at living-room coffee tables to unfold their plans and recite their memorized sales pitches, eager to close on a two-bedroom apartment with an ocean view, while maybe trying to hide their contempt for the place mats on the dining-room tables because they looked too much like the ones their parents used, whereas they were what? Thirty or thirty-five years old at the most, with businessmen’s attaché cases, pink shirts, and black patent leather shoes, trying hard not to look like their parents, who were of a generation with some pretty good years behind them, except that the stucco façades built twenty years earlier were showing signs of wear, and were eroding faster than the savings balance in their bank books. I know what I’m talking about. I used to have one of those bank books, too.

Did they know that my account recently got the four hundred thousand francs from the Arsenal? No, not the guys in the flannel suits. The moment I saw them making their way up the next street over, looking for all the world like Jehovah’s Witnesses come to talk about the Bible, I’d often duck down under my window while they rang my doorbell. When they stepped into houses, their eyes had that same strange light as if they were bringing the word of God. Except that instead of God, they had Lazenec.

That’s right, Lazenec. You would’ve thought he’d planned it all since forever, as if when he was fifteen or seventeen he’d written everything out in a kind of diary covering the next thirty years, and it was sufficiently fixed in his mind that he didn’t doubt for a minute that he would get what he was after. On that score, experience has taught me that everything depends on the chisel you use to carve the marble that serves as our brain. And it all depends on how hard you press the chisel. In his case, I’m sure he didn’t hesitate to press very hard inside himself and never strayed from the mental groove that would get him where he wanted to go and sweep us along with him.

Yes, sweep us along, I often thought as I looked at the estate’s five acres spread out under my window, which were beginning to reshape themselves vertically in our heads—and only in our heads—by dint of words like “duplex,” like “solarium,” like “fitness.” One day a billboard was put up at the estate entrance that had this written on it, I swear: “Coming Soon: The Saint-Tropez of Finistère.”

Today I don’t know if it hurt me to have gotten what you might call special treatment, I mean not having to deal with the little commercial agents paid on commission, every word out of their mouths like a barnacle stuck to a whale. In a way, I had the strange privilege of talking to God Almighty instead of his saints, because Lazenec came onto his property so often. That was another thing I had to get used to, the fact that the château, something that had belonged to everyone for three centuries, was now the property of just one person who came every week, or almost, accompanied by swarms of guys in neckties, for soil studies, or the land registry, or what have you. As time went on, he started calling me by my first name, and later still to greet me with a hug and kiss.

You heard that right, I told the judge, he started kissing me. You’ve been in the South of France, so you must’ve seen plenty of guys who kiss everyone in sight while holding a knife in their other hand. We like to think that just happens down south and not here in the north, of course. But even if you know full well that there’s nothing reassuring about a guy who hugs you so warmly, even if you have that stamped in black on white deep in your skull, when it happens to you, it’s not the same.

Maybe Le Goff was right, maybe I had been too isolated recently. The first person to break through that loneliness, you don’t give a damn who it is, so long as you take it all in and it fits you like the piece of the puzzle that y

ou could have cut out on purpose to perfectly fit your soul. That’s just the way it is. And that’s maybe the main thing I’ve learned in these last ten years: You always wind up loving the ones who love you.

This isn’t something I would’ve told you back in the day, but I’ve had time to think recently, time to look at the scratches in the mirror above the fireplace and to meditate on the color of each hour, I’ve had time to realize that I was like rich compost at the best planting season, where anything would’ve taken root in me and opened and flowered like at a garden show, to the point that I think Lazenec and I became friends, as it were.

But I hope you heard when I said “as it were,” because in reality you’d have to stick in a big silence, open an enormous parentheses that you would leave empty, just filled with the stink that was starting to hang over the harbor. I swear I’ve gone over the process a hundred times in my head, I told the judge, trying to see just when things between him and me went off the rails, and after six years, here in front of you, all I’ve come up with is to add “as it were.” Because it’s a problem that can’t be solved, when somebody like him approaches you, to know exactly when the sting happened.

I’m pretty sure I then looked up at the ceiling, which seemed to serve as our sky, over our entire world, the judge’s and mine, contained in that office.

Just the same, there must have been a beginning for you, he said.

Yes, that’s true, there was a beginning for me, or I should say a flaw in me. There was a flaw in me and he blew into it like the wind, because he was always blowing as hard as the wind, always working his way into any crack or fissure of the false front I had put up and was trying to pretend was brick, but the fact is, I’m not made of granite. Otherwise how can you explain the fact that I wound up in the passenger seat next to him in his Porsche one day, driving on the highway along the sea to go have a beer in the harbor, the only reason being to talk about fishing and especially boats, since he’d just bought a boat, the very kind that I’d been thinking of buying with the money from the Arsenal. What a coincidence, I’d once said to Lazenec, because I was thinking of getting the very same model.

How could I have known that right there, my saying that one thing among a thousand other things I’d said, with him standing at my front door about to leave, as usual, when we were talking about fishing, as usual, that I had the misfortune to tell him that I too was thinking of buying a thirty-foot Merry Fisher? How could I have known that with just those few words, I could bring myself so much bad luck?

Actually, that wasn’t the bad luck. The bad luck was that I hinted I had the money for it, that I could do it. And Lazenec wondered how a guy like me could afford to buy himself a Merry Fisher.

Right away I saw that he was thinking something like that, from the way he made his face blank, freezing it a little to hide his surprise. And then he asked a question in his roundabout way, with just the right touch of condescension: Secondhand?

No, new, I said. I plan to buy a new one.

He just stood there without saying anything, except maybe his shoulders twitched a little. What would you have done if you were in my shoes then? I asked the judge, if you’re looking at a blank face that seems to be expecting you to come up with explanations? Because that’s what happened. I imagined he was thinking things and I imagined I had to answer, that I had to justify myself to him, how it was possible that I, Martial Kermeur, a shipwright at the Brest Arsenal, could afford to buy himself a brand-new thirty-foot Merry Fisher? So what do you suppose I did? I told him the whole story. About my being laid off, about all the guys in the region getting their bonuses, about my four hundred thousand francs in compensation.

I could tell that this interested him a lot, and do you know how I sensed that? Because it was the only time I ever spoke for more than a minute at a time without him saying anything. He didn’t say a word, just listened to me without asking any questions, I don’t know, maybe like when you go see a psychologist for the first time and you tell him your story, and he lets you roll it out like a red carpet under your feet. But standing there at my front door, how could I have known that I was rolling out the red carpet for Lazenec?

Still, he left that evening like nothing was out of the ordinary. He got behind the wheel of his Porsche as usual and left. And do you suppose he approached me directly after that? I asked the judge. Of course he didn’t. Besides, do you think I would’ve given in so easily? No way. Quite the contrary. He let as much time as necessary go by after that, letting the days pile up and cover the things I’d said so I’d forget them and, worse, forget that there might be a connection between them. It’s only now that I’m thinking about all this in front of you, that I’m gathering my memories and lifting the veil he was able to lay down and stretch far enough to scatter the pieces underneath it.

We were in front of the château about a month later, talking fishing and boats again, and he mentioned the Merry Fisher he’d just bought, and I didn’t see the connection he’d made in his head. For him this was a good excuse to act friendly, and that’s what he wanted, to act friendly, friendly enough so that we’d eventually wind up standing in front of his new boat.

And that’s what happened. He drove me to the harbor in his Porsche. He put some awful music on the car radio and we crossed the bridge over the harbor. On Dock A of the marina we stood for a long time, arms folded, in front of a Merry Fisher 930, calmly chatting, yes calmly, because a dock in a harbor can calm the whole world, especially if you go there right at six in the evening when the sun is setting over the channel and flashes its great cutting light before disappearing.

We could see our château bathed in all that light, standing above the calm water on the other side of the harbor, standing there as if for all time.

From here, you’d think it was a real castle, I said.

That’s true, he said. It’s almost a shame to tear it down.

Tear it down? I asked.

While I was still digesting what he’d said, he was already walking toward the quay. I followed him, trying to say that I didn’t understand, that on the scale model it seemed that the castle—

Yes, he said, but what can I say? The project is evolving. Besides, Kermeur, it’ll be much more beautiful this way, you’ll see.

And I followed him up the gangway without quite knowing what to think. But at moments like that, Lazenec was thinking for two, as we walked away from the boats’ silent masts and went to sit on the terrace of the only bar open in the marina, which was like a mezzanine above the sea. And to be honest, when a guy like that invites you to have a beer, I told the judge, you never know if he’s doing it just because he’s alone that evening, or because he has something in mind, or maybe because he’s proud of himself because you’re the last person he would have thought to bring there, and he’s feeling proud at condescending to you. Since then I’ve understood that a guy like that always wants to have his cake and eat it too, and for Lazenec, eating the cake meant being friendly toward me for a while. And I sort of went along with him in that friendship.

In the end, you and I are kind of similar, he said. We’re like two estate managers, each in his own way.

I think I must’ve pursed my lips dubiously, to agree but also to not pick up on the point. He continued looking off in the distance, and you would’ve thought that just by looking he’d already erased the old building that served as our château, and I in turn could see it gently fading into the future, while he was saying that the advantage of the region was that the price per square foot was still affordable, and it was stable, and this was the sort of place where you couldn’t lose money, in fact it was the opposite because thanks to investments like his the price per square foot would rise, not to mention the economic fabric of the peninsula. I listened to him make his speech, with that manner he had of acting as if he was just mentioning all these stories about real estate and a bright future to me, but they really d

idn’t concern me, that is, he mentioned it with a kind of casualness. Notice his casualness, I told the judge. Here’s a guy who’s talking to you but could well not talk to you, and giving you the impression that everything he’s saying is happening somewhere else, far away, without you, so by the time he’s finished, if he’s done everything right, all you want is to be part of it. Lazenec knows that, he knows that’s the way it works.

Now I’m telling you this today as if I had all the clues in hand from the very beginning, but of course it wasn’t like that at all, I was as blind as Saint Paul after he fell off his horse. And I couldn’t tell you the way things followed one after another, the way the weather shifts into a string of rainy days. It was more like a fog bank moved in without our knowing when it started or what part of the road it covered. That evening I felt that everything was being enveloped in one slow movement, like a tightly spun cloth where you can’t make out the weave, because of the way things he said were being laid down like sediment on the bottom of a river. So it was no accident when he spoke up, interrupting himself, to say: You know, Kermeur, I think I owe you an apology.

An apology? I said. Whatever for?

Because I haven’t given you a chance to invest.

He said this as an offhand remark, maybe out of politeness, or at least I thought that he said it that way because there was already a bill on the table to pay for our beer, and I didn’t yet know that a dozen guys like me had probably been drawn into the same scene, enjoying the same hours of friendship constructed for the occasion, and told not to miss out on a deal like this, a brand-new apartment with a view of the harbor.

It should be said that he never presented it as a place to live in. He talked about investment and return but never living, so it remained like lines drawn by an architect without any substance between them. In the two hours we spent there on the harbor in the cool of the late afternoon, I didn’t hear a single word about living or dwelling. It was as if words like “functional” or “bright” or “modern” were only created to complete the expression “at maturity.” I remember that I asked him: What exactly does “at maturity” mean? I’m not sure I understood his answer, but I remember that “at maturity” you could make a lot of money, something like a 10 to 12 percent annual return—and I’m not sure I quite understood that either—except that it meant a lot of extra money for the owner.

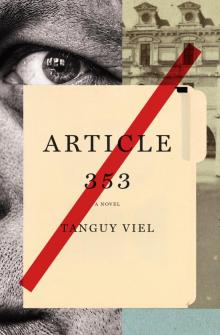

Article 353

Article 353